Was macht einen „Meister“ aus?

Verfasst: 03.02.2010 19:11

Hier ein interessanter Text von Errett Callahan, einem der ganz großen experimentellen Archäologen im Themenbereich Steinschlagen. Auf exzeptionelle individuelle Fähigkeiten und Charaktereigenschaften bezogen lässt sich der Text sicher auch auf andere handwerkliche Tätigkeiten aus dem Bereich der Archäologie übertragen. Neben lobenswerten charakterlichen und anderen geforderten Standards ist aber das spannende Fazit: Heutige Steinschläger können den Titel „Großmeister“ erreichen, diejenigen aber, die ursprünglich die Formen und Techniken vor Jahrtausenden entwickelten sind lediglich „Meister“?

"The following is an excerpt from the Bulletin Of Primitive Technology, p.9-10, Fall 2000: No.20.)

What is a Master?

by Errett Callahan, (Piltdown Productions Catalog #5, p. 11-12, 1999)

Mastery doesn't come with tools or tricks. Mastery lies in the hands and head. It's a matter of know-how and that takes time.

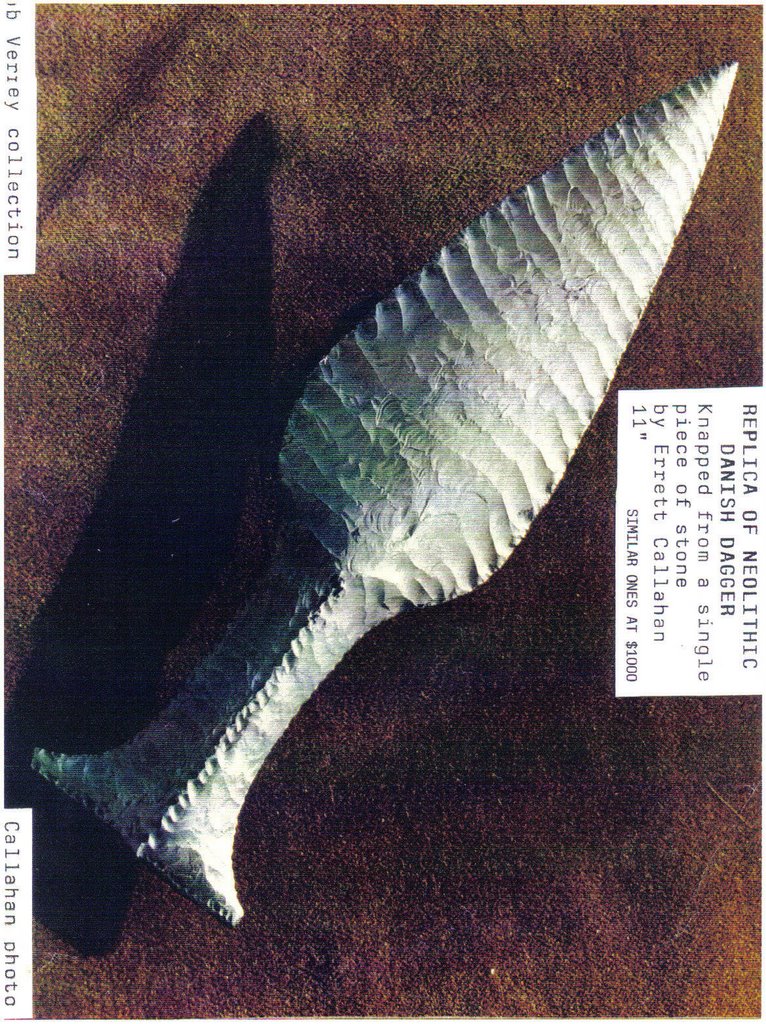

A master is one who can work at a world-class level in a traditional manner in a wide range of technologies. You don't get there by being good at any one thing, even if you're the best in the world at it. A master can handle the largest sizes with finesse, but size alone does not make the master. The flintknapping master is one who is fluent in both New and Old World technologies, one who can walk across time. He must be able to demonstrate competency at replicating Oldowan, Acheulean, and Mousterian technologies. (If you think the Neanderthals' Levallois work was easy, think again.) The Upper Paleolithic blademaking industries must be demonstrated without hesitation. The Solutrean laurel leaves must be replicated with the proper thinness and flake removal sequence. Mesolithic bladelets, microblades, and geometric microliths must be second nature. And Neolithic square work, mega-blades (over 30cm), and Danish Daggers must be replicated in all their elegance. That is, they must be replicated with the proper flake removal sequence and contours, not just simulated in their approximate shape. New World forms such as Clovis, Folsom, and the parallel-flaked Late Paleo points must be replicated as well as the Archaic and Woodland points and bifaces so beloved of many. And the Maya eccentrics and prismatic pressure blades must be demonstrated with confidence. And if they are knifemakers, their bifacial edges must be able to shave the hair off an arm and slice leather smoothly.

Yet mastery does not stop at acrobatic skill, no matter how talented one may be. On the one hand, one must be legitimate. Everything must be above board with no hidden cards under the table. Everything one makes must be indelibly signed and dated. On the other hand, the master must be a teacher. He must make himself available to students and not live in isolation. He must be willing to teach all he knows. He holds nothing back (unless the student's ethics are suspect). There are no secrets. And following the leads of Don Crabtree and J. B. Sollberger, as well as the martial arts masters, the master is modest, he has humility. You don't get that by patting yourself on the back. Humility above all else is the mark of the master.

The only living masters of flintknapping who I recognize are Gene Titmus of Idaho and Jacques Pelegrin of France. They have demonstrated to the world the vast majority of the above. They work with traditional tools in a traditional manner. And they are light years ahead of anyone else, myself included, and traveling faster. You don't get where they are overnight. It takes decades to become a master. But time alone does not a master make.

______________________________________

Mastery: A Reconsideration of Standards

by Errett Callahan

I have previously defined a flintknapping master as one who has demonstrated a certain rigorous depth and breadth of knapping skill, Old World and New, reaching across all time and space barriers. The definition also included certain standards of high character.

In reconsideration of certain high points of flintknapping in the prehistoric past, it seems that my original definition would have excluded from mastery the makers of the prestigious Danish daggers, the Maya eccentrics, certain Paleo and Late Paleo projectile point types, and other exceptionally well-made and challenging stone tools. This is because, although these artisans did what they did well, they only did their one thing; they did not work in world wide industries. I now suggest that for such single high points of prehistoric knapping, there should be a master skill level designation for ancient workmanship which lies beyond the journeyman level if the challenge is sufficiently great and the skill demonstrated lies at a world class level. Naturally, for prehistoric situations, standards of character may not be determined.

With modern knapping, the same considerations should also hold true, except that standards of character should indeed be considered. Thus a modern knapper, working in only one or a few industries, but doing so at a world class level, may be considered for mastery if the following standards, as noted in my 1999 definition, are taken into account:

1- One's ethical behavior is beyond reproach;

2- One is a teacher, passing on knowledge, sharing one's innermost "secrets" (once

the student is ready for them), and refusing to withhold knowledge (except to students

who are not to be trusted);

3- All works are indelibly signed and dated;

4- Work is done in a traditional manner;

5- Humility of attitude prevails.

According to these standards, mastery is forever banned for those of unethical conduct, including such fraudulent activities as passing off one's work as ancient or as being anything other than one's own -- no matter how skilled one may be otherwise.

Concerning traditionalism, there is no mastery, in legitimate flintknapping, for non-legitimate procedures. Such would exclude lapidary knapping. For those who prefer such procedures, let them create their own standards, but let them not have their work confused with traditional flintknapping, which is the only subject under consideration here.

The determination of who is a master must not be self-proclaimed or be voted upon by one's peers. Only other masters may determine who is a master.

In my original definition, I listed only Gene Titmus and Jacques Pelegrin as master-level knappers. I would now categorize them, and those who meet the same criteria, as described above, as "Grand Masters". It's now up to them to determine who are the new generation of master level craftsmen.

Until such time, perhaps the Board of Directors of the SPT may wish to initiate further inquiry in this direction, preserving the privacy of the Grand Masters."

Quelle: http://www.vortac.net/traditionalflintk ... llahan.htm

"The following is an excerpt from the Bulletin Of Primitive Technology, p.9-10, Fall 2000: No.20.)

What is a Master?

by Errett Callahan, (Piltdown Productions Catalog #5, p. 11-12, 1999)

Mastery doesn't come with tools or tricks. Mastery lies in the hands and head. It's a matter of know-how and that takes time.

A master is one who can work at a world-class level in a traditional manner in a wide range of technologies. You don't get there by being good at any one thing, even if you're the best in the world at it. A master can handle the largest sizes with finesse, but size alone does not make the master. The flintknapping master is one who is fluent in both New and Old World technologies, one who can walk across time. He must be able to demonstrate competency at replicating Oldowan, Acheulean, and Mousterian technologies. (If you think the Neanderthals' Levallois work was easy, think again.) The Upper Paleolithic blademaking industries must be demonstrated without hesitation. The Solutrean laurel leaves must be replicated with the proper thinness and flake removal sequence. Mesolithic bladelets, microblades, and geometric microliths must be second nature. And Neolithic square work, mega-blades (over 30cm), and Danish Daggers must be replicated in all their elegance. That is, they must be replicated with the proper flake removal sequence and contours, not just simulated in their approximate shape. New World forms such as Clovis, Folsom, and the parallel-flaked Late Paleo points must be replicated as well as the Archaic and Woodland points and bifaces so beloved of many. And the Maya eccentrics and prismatic pressure blades must be demonstrated with confidence. And if they are knifemakers, their bifacial edges must be able to shave the hair off an arm and slice leather smoothly.

Yet mastery does not stop at acrobatic skill, no matter how talented one may be. On the one hand, one must be legitimate. Everything must be above board with no hidden cards under the table. Everything one makes must be indelibly signed and dated. On the other hand, the master must be a teacher. He must make himself available to students and not live in isolation. He must be willing to teach all he knows. He holds nothing back (unless the student's ethics are suspect). There are no secrets. And following the leads of Don Crabtree and J. B. Sollberger, as well as the martial arts masters, the master is modest, he has humility. You don't get that by patting yourself on the back. Humility above all else is the mark of the master.

The only living masters of flintknapping who I recognize are Gene Titmus of Idaho and Jacques Pelegrin of France. They have demonstrated to the world the vast majority of the above. They work with traditional tools in a traditional manner. And they are light years ahead of anyone else, myself included, and traveling faster. You don't get where they are overnight. It takes decades to become a master. But time alone does not a master make.

______________________________________

Mastery: A Reconsideration of Standards

by Errett Callahan

I have previously defined a flintknapping master as one who has demonstrated a certain rigorous depth and breadth of knapping skill, Old World and New, reaching across all time and space barriers. The definition also included certain standards of high character.

In reconsideration of certain high points of flintknapping in the prehistoric past, it seems that my original definition would have excluded from mastery the makers of the prestigious Danish daggers, the Maya eccentrics, certain Paleo and Late Paleo projectile point types, and other exceptionally well-made and challenging stone tools. This is because, although these artisans did what they did well, they only did their one thing; they did not work in world wide industries. I now suggest that for such single high points of prehistoric knapping, there should be a master skill level designation for ancient workmanship which lies beyond the journeyman level if the challenge is sufficiently great and the skill demonstrated lies at a world class level. Naturally, for prehistoric situations, standards of character may not be determined.

With modern knapping, the same considerations should also hold true, except that standards of character should indeed be considered. Thus a modern knapper, working in only one or a few industries, but doing so at a world class level, may be considered for mastery if the following standards, as noted in my 1999 definition, are taken into account:

1- One's ethical behavior is beyond reproach;

2- One is a teacher, passing on knowledge, sharing one's innermost "secrets" (once

the student is ready for them), and refusing to withhold knowledge (except to students

who are not to be trusted);

3- All works are indelibly signed and dated;

4- Work is done in a traditional manner;

5- Humility of attitude prevails.

According to these standards, mastery is forever banned for those of unethical conduct, including such fraudulent activities as passing off one's work as ancient or as being anything other than one's own -- no matter how skilled one may be otherwise.

Concerning traditionalism, there is no mastery, in legitimate flintknapping, for non-legitimate procedures. Such would exclude lapidary knapping. For those who prefer such procedures, let them create their own standards, but let them not have their work confused with traditional flintknapping, which is the only subject under consideration here.

The determination of who is a master must not be self-proclaimed or be voted upon by one's peers. Only other masters may determine who is a master.

In my original definition, I listed only Gene Titmus and Jacques Pelegrin as master-level knappers. I would now categorize them, and those who meet the same criteria, as described above, as "Grand Masters". It's now up to them to determine who are the new generation of master level craftsmen.

Until such time, perhaps the Board of Directors of the SPT may wish to initiate further inquiry in this direction, preserving the privacy of the Grand Masters."

Quelle: http://www.vortac.net/traditionalflintk ... llahan.htm